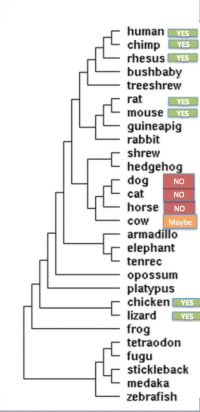

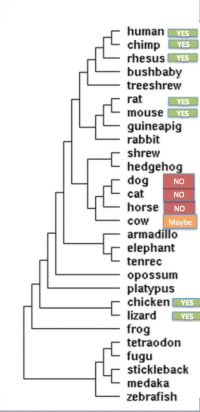

Lots of animals get malaria, including birds, reptiles, snakes, primates, bats, rodents, and at least one ungulate, the antelope. Even turtles get Haemoproteus parasites, a phylogenetic sister species to those in the Plasmodium malaria parasite group. So why don’t cats, dogs, and horses get malaria? There are also no documented cases in pigs that I could find, and with a questionable exception of a case in a water buffalo, bovids may also be exempt.

I started looking for similarities among animals that haven’t had malaria.

One of the most important organs for humans and rodents in fighting malaria parasite infection is the spleen. In a bold statement, one researcher suggests that the evolution of spleen structure may have been driven by malaria parasite infections. Primates and rodents have a defensive type spleen. Looking for differences among spleen morphologies seemed like a logical place to start.

I found that canids and equids have in common “storage type” spleens, called dynamic sequestering spleens where they store blood and have drastic changes in hematocrit with exercise. Cats also have this type of spleen that works as a dynamic sequestering organ for blood. How much blood is being stored? Horses store up to half of their RBCs in the spleen, and dogs store 1/3, changing hematocrit drastically when going from resting to exercise. Cats may store 20% of their RBCs in their spleen. In contrast, our hematocrits change maybe 5% with exercise, and no more than 2-3% of this change is due to the spleen, the rest is from water moving to our muscles.

So, is it a coincidence that animals that have dynamic sequestering spleen are malaria-free? Correlation isn’t causation, and since horses, dogs, and cats share a closer phylogenetic history than the rest, it is difficult to sort out whether lack of malaria parasite infection is because of spleen morphology or other shared features.

The spleen isn’t a commonly discussed organ (there’s even a paper called “The avian spleen, a neglected organ” by J.L. John in 1994, which states that bird spleens don’t store red blood cells). However, the spleen removes parasitized red blood cells, is involved in making new RBCs, has immune functions, and plays a large role in malaria clearance. So, is it spleen evolution or morphology the reason horses, cats, and dogs don’t get malaria? And could it be that rapidly shifting hematocrits stop these parasites?

I was asked to give the Commencement Speech at the Graduate School ceremony. That’s about 2,000 students getting advanced degrees plus their families. It’s an odd thing to be asked to do. The invitation letter read: “I am confident our graduates and guests would have significant interest in your own life story and the experiences, factors, or personal characteristics that have most contributed to your considerable achievements.”

I was asked to give the Commencement Speech at the Graduate School ceremony. That’s about 2,000 students getting advanced degrees plus their families. It’s an odd thing to be asked to do. The invitation letter read: “I am confident our graduates and guests would have significant interest in your own life story and the experiences, factors, or personal characteristics that have most contributed to your considerable achievements.”

I just finished reading

I just finished reading