Monthly Archives: February 2015

Think different

I am often fascinated by how similarly everybody thinks. For example, people have a harder time comparing fractions than comparing decimals. If I asked which is larger, 3/25 or 7/56, you would almost certainly have to think before answering, whereas you likely wouldn’t be challenged at all if I had asked the same question in decimal form (0.12 vs 0.125).

My more recent fascination comes from an observation in games like charades and pictionary. Why is it so easy to depict an adjective (for example, blue or happy) but so hard to depict an adverb (for example, quickly or sadly)? How much of this difference is cultural and how much of it is hard-wired into the way humans think? Would an intelligent alien species have the same bias? Apple’s advertising slogan used to be, “think different”. I wonder if it might be possible to train people in science to instead “think differently”.

Herbal medicine percolating into PNAS

Around this same time last year I wrote a blog on the subject of whether drug resistance evolves as readily against whole plant medicinals as it does in response to single component drugs — “Before drug resistance was there plant resistance?”

My question has been partly addressed by findings PNAS published in December (Elfawal et al.): “using the whole plant (Artemisia annua) from which artemisinin is derived can overcome parasite resistance and is actually more resilient to evolution of parasite resistance; i.e., parasites take longer to evolve resistance, thus increasing the effective life span of the therapy.”

Steve Buhner has touted that whole plant medicinals act as the original combination therapy for years. Perhaps a more surprising result would be to find a case where the opposite is true — anyone know of a plant where efficacy of an active component might be masked in whole plants because of the presence of antagonists rather than agonists?

Artemisia is not the only plant that herbalists have argued could be acting as combination therapy and this presents an interesting idea that Dave and I were discussing at the bar last night: why should plants contain more than one compound that acts against a human parasite?

My best answer is that perhaps plants that are better suited for treating malaria (i.e. wormwood, cinchona bark) are plants that have evolved defenses to plant-infecting protists that are like a plant-version of malaria. Plants that are used as herbal antibiotics may be the plants that historically were more likely to succumb to bacterial infections and thus have multiple defensive compounds that target bacteria, whether human-infecting or plant-infecting. How many human infections may have a look-alike plant infection? And could understanding which plants are exposed to and have defenses against certain plant diseases help predict which plants will best function in fighting a complementary human disease?

I’m reading more of Steve Buhner to try and gauge the extent to which this could be true. If anyone else is interested, I’m happy to lend a few of his books: Herbal Antibiotics and Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm.

Fun fact about Buhner: his great-grandfather, an herbalist from Indiana, became the Surgeon General of the United States under Eisenhower and Kennedy.

Putting some numbers on the local disease outbreak: measles

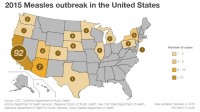

I want to bring attention to the recent measles outbreak. Pennsylvania is one of the 14 states where measles is spreading right now. This map is from February 2nd, 2015, only 4 days ago.

I imagine these numbers have changed already, and will continue to increase.

The “epicenter” for this 2015 outbreak is Disneyland in California, a tourist destination.

There’s a lot of emotion about vaccines. This physician’s impassioned blog communicates these feelings and also why not everyone can be protected by vaccination. Age is common reason – those under 1 year old have weakened immunity and can’t receive the MMR vaccine. That’s roughly 120,000 kids in PA, or roughly 4,360,000 kids in the USA. To count this many kids by saying numbers aloud would take more than 100 days with non-stop counting day and night. That’s a lot of people who can’t be vaccinated against measles.

To establish herd immunity we need enough converts to get vaccinated. Pennsylvania is ranked the second worst vaccination rate for the MMR vaccine in the country, roughly 10 percentage points lower than the 95% required for herd immunity.

Confessions of a research evangelist

On my mid-morning visit to the post office last week, I met a former student of mine. We greeted each other enthusiastically, I was really pleased to see him. Despite not being a star student, he had nevertheless really tried – just the attitude you want. For weeks in a row, he had come to my office hours with good questions and talk of his ambitions to be a neurologist. The first question I asked him in the queue was, ‘So, are you doing research?’

I doubt he was surprised. Just as when I worked in a library, it was my mission to convert just one child from free DVDs to free books, when I TA a laboratory section I aim to get a few of my students doing research. The first time you mention it, they look at you like you’re crazy. But I try to make the idea of undergraduates doing research normal. When we review micropipetting I teach them ‘tips and tricks that would be really useful if you join a lab’. I introduce new topics by referring to Penn State faculty that work on the subject ‘if anybody’s interested in finding out more’. Particularly with the students that struggle, I tell them that research would increase their confidence. Now, come the fourth week of the semester, students have started to hang behind after class or send me emails to ask me about getting involved with research. The main things they say are ‘I don’t know how to go about it’ and ‘Is it too early/too late to start?’.

The last question is easily answered with a quick ‘absolutely not’, though I’m of the belief that the earlier a student starts working in a lab, the better. And how to get into research? It seems so simple: just google ‘Penn State’ and the subject you’re interested in, read the faculty members’ blurbs, choose one, make sure they don’t have an ‘undergrads not welcome’ sign on their door and send them a short email. The problem is that most of these students can’t imagine what ‘research’ looks like, let alone think it’s for them. They are astounded when I tell them that really, it’s as simple as that. Some of my students just need to hear what my Mum always told me, ‘Go for it! The worst they can do is say no’. The thanks I receive from students for doing the googling step for them and emailing along the results, are incredible. In terms of the time-invested: satisfaction ratio, this ranks pretty highly.

And so to the guy in the post office. He was queuing up to send off an application for a summer research project at another university. Just the previous week, he’d started working with a professor whom I rate very highly and was due to start running an experiment with him, working one on one, that weekend. In this student’s case, I don’t know if I had a role in making this happen but I was delighted, anyway. One more for research!

Tweeting

Last week, Matt forwarded me an e-mail for a “careers in tropical medicine” type event that is being hosted, of all places, on Twitter. Given Matt’s general opinion on social media, the idea that he would recommend anything on Twitter was surprising. Naturally, this raised the question of when we can expect @MattThomas to make an appearance on Twitter and I have to report that it seems unlikely to happen any time soon.

After a brief perusal, Matt said that he would consider joining if I could show him some tangible benefit from being on Twitter. There are some relatively well-known and respected people in the field who are active on Twitter, and a few have written about why they find Twitter useful. But I doubt that there’s a single instance where Twitter has made a substantial difference in somebody’s career. If anybody has an example please let me know, I’d be interested to hear about it.

As for myself, I’m a Twitter agnostic. I maintain a presence because it’s easy enough to do and it’s an additional avenue to maintain a professional presence on-line, but I don’t derive any particular enjoyment from it. For maintaining a non-professional (but I like to think not un-professional) social media presence, I actually prefer Facebook. In this preference, it turns out that I’m showing my age.

So why Tweet? As a Twitter agnostic, I’m not going to try to change your mind one way or the other, but I will say that I see it as the electronic equivalent of attending conference happy hours. It’s a way to maintain connections to people you already know and maybe make some new contacts, but it’s highly unlikely that someone is going to offer you a job on the spot.

Parched

“This would be a good country,” a tourist says to me, “if only you had some water.”

He’s from Cleveland, Ohio.

Edward Abbey opens a chapter of his book Desert Solitaire, with a short conversation that really encapsulates the remarkable situation that characterizes the Southwest: massive cities, massive populations; both arising on arid, water deprived land – a stupefying, unnatural demand for such an environment.

I recently saw a talk given by Glen MacDonald, a Professor of Geography at UCLA, and what he said and how he said it, staggered me. I’ll quickly remark here that important issues necessitate good speakers, and if there was ever a reason for a graduate student to improve their skill in giving talks, this is it. Important issues will not resound with the public unless they are presented with shattering clarity. I’m glad climate change and water resources in the Southwest have a speaking voice through Professor MacDonald.

The water situation in the Southwest is more than dire. We are currently amidst a major drought that has taxed the Colorado River basin to its limits in its ability to provide water for cities in Arizona, California and Nevada. Lake Mead, a reservoir in Nevada that serves as a gauge for water availability, is nearly at a level that would require the federal government to initiate a mandatory rationing program in some states in the Southwest. The drought is not fueled by decreases in precipitation, but rather increases in evaporation due to climbing temperatures. Surprisingly, it’s not Jacuzzi’s and perfect manicured lawns that suck water from Lake Mead. According to Dr. MacDonald, 80% of water use (at least in Los Angeles) is used for agriculture maintenance. Feeding our population is heavily water intensive.

Dr. MacDonald went on to say that predictions on the length of the current drought are fraught with uncertainty, but if history can tell us anything, it is that droughts can last an immensely long time, and they have done so in the past. The question remains, what happens when these long term droughts hit now, when we have such massive developments? I think we need a massive rethink on how we are managing our water.

As scientists, we certainly have an obligation to present our field of research well and with passion, but I also think that we have a certain obligation to keep ringing the bells on important issues. This is important. I say we keep talking about it. We may not be experts as infectious disease evolutionary biologists, physicists, statisticians or biochemists, but as scientists and people who inhabit the earth, we need to be interested in how we mange it.