In my role as bridge vector between our research group and the seamier side of OPP and EHS I have, while trying to maintain up to date knowledge viz a viz health and safety, taken any number of courses and read all sorts of pamphlets appertaining to life in the laboratory. Recently one such document caught my attention. Put together by a special EHS sub-division (Services for Health, Environment, Employee Trauma and Ennui) the authors had looked into and subsequently produced a report on “Alternative Late Night Laboratory Companions: A Guide to Non-Humans.”

Being familiar with the echo of empty laboratory corridors I have often felt, as I am sure you have, that in the absence of a colleague a bit of alternative, but still real-life conversation would be more desirable than having to load yet another Barbara Cartland onto the ipod. A whole report assessing the conversational abilities and other merits of non-human animals as late working companions was definitely something to peruse and report on to the group. So I dipped into the weighty volume and came upon the section headed “Domestic Fowl,” which started enthusiastically by stating:

“Everyone loves chickens. Be they Light Sussex, Rhode Island Red, Longhorn Leghorn or, praise be, a Buff Orpington Cock. Conversation is never dull in the lab when there is a chicken around. They have that knack for small talk that makes a long day at the microscope fly. Even if they can’t.”

Despite this high praise the section goes on to conclude:

“However, chickens cannot be recommended as companion animals in the laboratory. Though their conversational qualities are well documented they are wont to preen.”

In the same section ducks get short shrift as they are “inclined to waddle” a distracting behaviour the author notes, “which can be much better observed at Walmart.” Geese receive the most scathing assessment:

“Geese have no saving graces in the lab. They are haughty and inclined to a variety of neuroses which, over the course of an evening spent sorting pupae can be overwhelming. What is more they regularly sod off somewhere north. You might be on your eighty-first dissection and in dire need of a good chinwag, when there is a sudden flapping of wings, your notes get buffeted into the chloroform jar and all your carefully prepared samples end up in the fag ash on the floor. The geese meanwhile depart for Svalbard and a summer of sex and sunshine.”

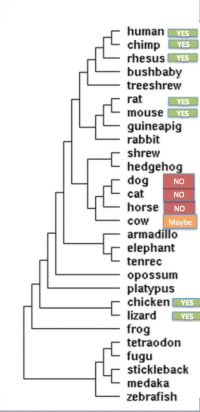

Mammals barely figure in the report with cats being described as “only wanting to talk about foreign policy,” horses “lugubrious in the extreme” and porcupines “prone to emotional outbursts.” I feared dogs might be discussed but thankfully all they authors say is; “Dogs cannot be seriously considered as companion animals as they have no conversational ability whatsoever.”

As if the latter really needed pointing out. Finally I found the important section:

“One might consider fish,” the document stated. Yes, I do. Often, I thought. “The particular choice of laboratory companion fish is a difficult one. Some swear by carp. They are intelligent, thoughtful and ruminative conversationalists. However, the pace of their discourse is not to everyone’s taste. For those inclined to snappier repartee the experts suggest one of the cleaner wrasse. Naturally cleaners, given their original job, have the full hairdresser type repertoire complete with a range of put-you-at-ease entrees, a lightening quick ability to change topics when the previous one flags, a surprisingly thick skin for those awkward moments and the ability to make a really good cup of tea.”

Excellent, we should get one for the insectary I thought. But then I noticed an addendum:

“Beware however, the Fang-toothed blenny, the cowboy of laboratory conversationalists. They may look like wrasse and even act like wrasse but once let in the door turn out to be surly, uncommunicative and if pressed, prone to violence. While this may increase the excitement, losing your focusing finger will not facilitate the oocyst counts.”

There was much more but in the end I had to settle for the disappointing fact that, what with the variety of options available and the lack of any clear choice, the lab would have to continue to echo with the earnest tones of NPR’s “This American Loofah.”