I recently read this blog post on how to review a paper. I thought it was a good summary, although that’s probably because it happens to fall in line with my own reviewing philosophy.

Monthly Archives: April 2014

Coffee break science

bs()ing my way to a degree (3 polynomial)

When I first arrived at Penn State, one of my advisors (Ottar) kept mentioning splines, and I had no idea what he was talking about. In my time here, I’ve grown to know and love splines, and I’m going to share that joy with you now, if only so you can fully appreciate the title of this blog post.

People had to make elegant curves for engineering purposes long before there were computers, and splines were a perfect way to get a smooth curve anchored at certain points, called knots or ducks. When building boats or planes, people needed smooth curves on a large scale, so they had to loft their splines above the work area. This “lofting” started to go purely mathematical during World War II. Clever folks worked through the mathematics of splines, and other folks developed handy packages in R, making splines portable and available to the masses.

I first came to know splines as an easy way to smooth over those pesky gaps between discrete data points. Let’s say you have data on mosquito longevity at 24, 26, and 28 degrees Celsius, but in order to make a map of Africa (Becky) you need to make an educated guess about what the mosquito longevity will be at 27.35 degrees Celsius. You can make a spline to connect the dots, while specifying the degrees of freedom (i.e., the wiggledy-ness)–that’s a job for smooth.spline() in R. If you just want a function so that you can figure out how quickly mosquito longevity changes at a particular temperature, there’s always splinefun(). It’s so-named because it makes the spline object into a function that’s easy to evaluate and differentiate, but I know in my heart that it’s truly meant to allow me to derive the maximum fun out of splines.

More recently, I’ve been dealing with spline basis functions using the aptly-named bs() function in R. These basis functions have some beautiful properties–you feed bs() a series of x values, and it gives you basis functions over those x values. The basis functions are like puzzle pieces, and you can combine them in different ways to create any polynomial function. For example, if you you want the spline basis functions to create a degree 3 polynomial (cubic, my favorite), you just specify degree=3 when you ask bs() for your spline object. It sounds mysterious, but sometimes you don’t know the shape of the function you’re looking for: What will the optimal life-history strategy look like? What strategy is suggested by the data? In that case, a mysterious spline object (and a robust optimization algorithm) could be your new best friend. I’m profoundly grateful for easy access to spline machinery, without which my scientific pursuits would be entirely out of reach.

NPR why are you editing out mosquito control?

I’m a NPR nerd. Morning edition and coffee power my morning. So imagine my delight when I turned on my radio this morning to hear the voice of Bill Gates (billionaire philanthropist) pronouncing one of my very favorite words, “mosquito”.

If you listen to the audio of this interview you will hear Mr. Gates talk about mosquito behavior as being an important area of advancement. He says, ” The thing that’s magical now is that we’re able to look at the malaria genetics and understand how it’s spreading and so how do you repel the mosquito we understand.”

NPR has edited the print interview for “clarity and length” and Bill’s answer to his question reads, “Those Nobel Prizes were given a long time ago. The thing that’s magical now is that we’re able to look at the malaria genetics and understand how it’s spreading. … “. They go on to edit out an entire section in which he explains the importance of climate for mosquito population dynamics.

WTF NPR?! You have just turned one of the most powerful men on the planet saying my work is important (and fundable) to a “….”! Mr. Gates presented a pretty well rounded approach to malaria eradication that touched on mosquito ecology, advances in genetics and understanding of disease dynamics, and efforts to create a good vaccine. The editors on the NPR website has cherry picked this to read as though he said we should sequence everything and that a vaccine with a 30% efficacy will fix the problem. There is now not even one mention of the word mosquito in the print interview.

Disappointing.

Fielding questions via snail mail

I hardly ever get mail. It is 2014 so all the important stuff goes through email inboxes, only leaving paper mail for things like bills, the State College “Valu Pack” and the extra subscriptions to Family Circle and Reader’s Digest that my grandmother subscribes me to (she says they give me good things to think about).

This week my mom sent me something. It came in what looked like an Easter card, only inside it said: “I am sending you a bug.”

Inside:

And out falls this little guy:

My mom is asking me, family scientist and therefore default expert on all matters biological — insects included — if I can tell her what it is.

In my quest for ideas, I take my lunch break in the Hughes lab to use their dissecting scope equipped with a camera. Take a look:

The antennae appear to have snapped off. Other clues: it was removed from a dog, found in upstate New York, found during spring season, is attached to what appears to be plant material (perhaps some type of grass). Any ideas?

My instinct says “tick,” but what kind? I submitted a picture to the Tick Encounter Resource Center. I am trying to beat them to the identification so feel free to stop by my desk and take a peek. Tick expert or just curious, maybe give me some advice on how to ID? It won’t bite!

If we could kill all of the mosquitoes in the world, should we?

This 22 minute Radiolab podcast poses this question, and discusses it in the context of mosquito control and insecticide resistance.

This 22 minute Radiolab podcast poses this question, and discusses it in the context of mosquito control and insecticide resistance.

An article called “Sympathy for the Devil” by David Quammen (interviewed in the podcast) brings forth an argument suggesting that some mosquitoes are important pollinators, and so not all mosquitoes should be killed.

Yet, here’s a 2010 article in Nature by Janet Fang that suggests the world would be just fine without mosquitoes and that any pollination services they provide aren’t important for plants we care about (namely agricultural crops).

I’m not convinced that our collective human disinterest in mosquito-pollinated plants justifies their elimination from Earth. However, I also think it would do a lot of good with minimal harm if we eliminated the mosquito species that transmit pathogens. Your thoughts?

Harbinger of Spring

Someone had the lovely idea of planting daffodils on campus. Seeing them makes me happy and reminds me that days of sunshine will soon be here.

Daffodils

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.

Continuous as the stars that shine

And twinkle on the milky way,

They stretched in never-ending line

Along the margin of a bay:

Ten thousand saw I at a glance,

Tossing their heads in sprightly dance.

The waves beside them danced; but they

Out-did the sparkling waves in glee:

A poet could not but be gay,

In such a jocund company:

I gazed–and gazed–but little thought

What wealth the show to me had brought:

For oft, when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude;

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the daffodils.

ΠηΔ (that’s PhD in Greek)

I never pledged a frat, but I find it funny that many academics have a negative opinion of frats, because the similarities between pledging and grad school are striking:

1) You can’t start pledging unless you have been given a bid by the current brothers. You can’t get a PhD unless you have been accepted into a program by the current PhDs (faculty).

2) You can try to argue, but ultimately you have to do what your pledge master (or advisor) says.

3) Lots of requirements seem unimportant, but you have to follow them to finish.

4) Your liver will hate you.

5) Surviving the process isn’t enough to guarantee acceptance. At the last second, the current brothers (or your committee) get to decide whether you completed it well enough to pass.

6) Pledges have “hell week”. PhD candidates have “writing up”.

7) Shared pain creates strong friendships between members of the same pledge class. Shared pain creates strong friendships between members of the same cohort.

8) Frat brothers get nostalgic about pledging. PhDs get nostalgic about grad school. Both are misremembering.

9) Frat brothers tend to hang out with other frat brothers. PhDs tend to hang out with other PhDs.

10) Frats have mixers where members of multiple frats/sororities meet and get drunk. PhDs have conferences where PhDs of multiple universities meet and get drunk.

Differences between joining a fraternity and getting a PhD:

1) Pledging lasts one semester.

Conversation piece

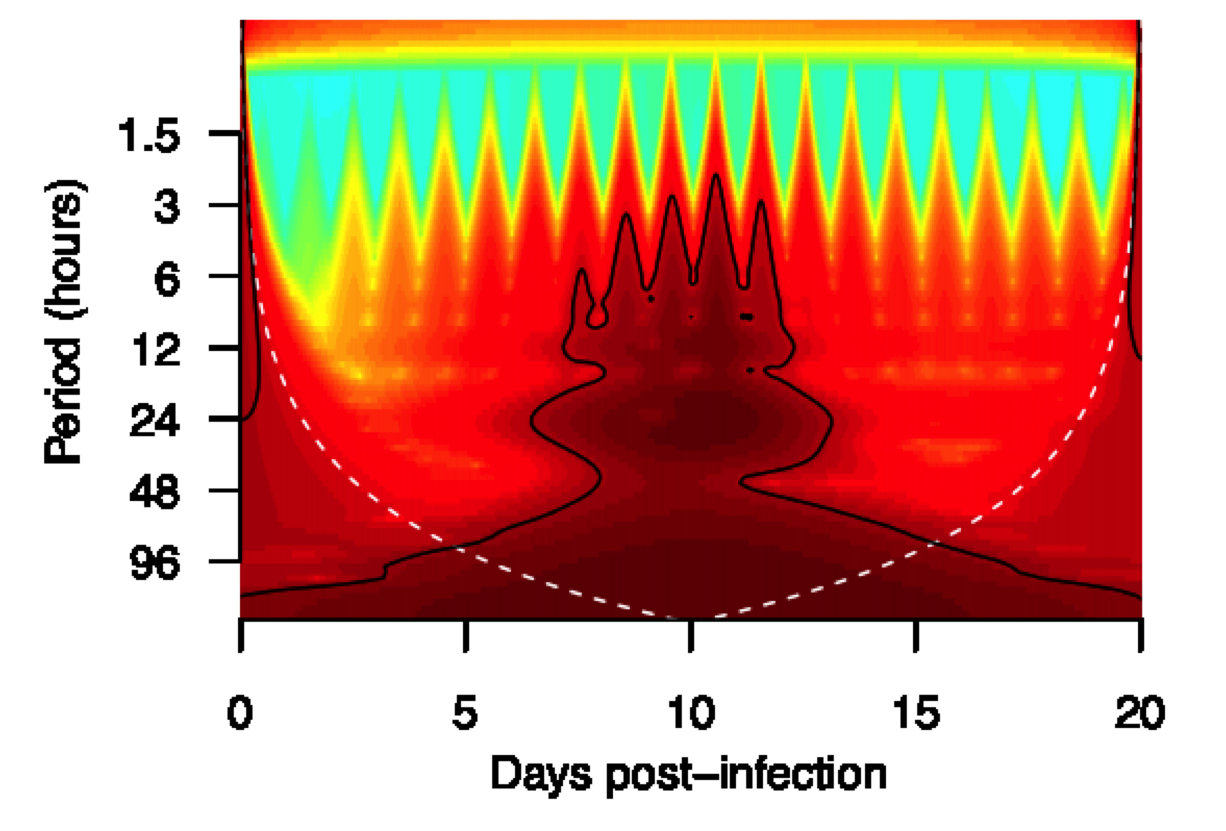

I firmly believe that pretty pictures are an integral part of science. I tell myself that spending lots of time making clear and appealing figures will help me communicate my ideas, but really, I just enjoy making figures. Here’s a recent example:

It may represent a cunning way to tell whether malaria parasites are changing their transmission investment over the course of an infection, or it may end up being wall-art with no deeper scientific meaning. Either way, I work in an open office environment, everyone (and I do mean everyone) can see my screen as they enter the computational area, so in some sense I have a captive audience on which to test my visual efforts. Even if it turns out to be wall-art rather than scientific advancement, I count this one as a win because it drew two separate people into the cubicle to see what I’m working on.

* OK, so one person found it just disturbing, but she still came over to see what I was doing.

Dispatches from the field: Part II

After our first, unsuccessful, foray into the field last Friday, we headed back out with better luck on Monday. There was indeed a cattle cart to meet us, which we loaded with gear and then got on board. That’s three European scientists, three Tanzanian scientists, a research technician, two drivers for the trucks we took from IHI, a large crate of equipment, and me. All piled into one cattle cart.

Ten minutes into the ride and we’re stuck in the mud again. Not only are we stuck, but the yoke holding the four cows in place has snapped in two and the cows have run amok.

We all climb out of the cart and the cart driver fixes the yoke while his son runs after the cows. With two of the four cows back in place, the much emptier cart makes it out of the mud. To prevent another break down from our collective weight, we trudge behind the cart in knee deep water and mud, all the way to the village.

After we’ve finished our visit, the cart driver brings around what turned out to be a sturdier cart, which we ride all the way back to the rangers without another break down.