Last week was officially my last week as Andrew´s postdoc. Truly last this time round, though with much work still left undone, this won´t be a goodbye message. I´ve learned a lot over the nine (!!) years since I started in his lab as an MSc student. One of these things is to go out and network. I believe it is a very important skill in science. It is something that comes more naturally to some than others, but it is definitely a skill that can be learned, though it will require courage.

What will you do? Seize the opportunity or hide in the bathroom?

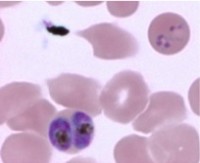

I again realized the importance of this during a meeting I attended over the past two days. It was a small international meeting on the topic of antibiotic resistance, extremely interesting. At the same time, I felt very much out of depth in this crowd of mostly clinicians, hardly understanding the field-specific language of abbreviations for any bacteria, antibiotic, mutation, cut off point they know. In addition, I hardly knew a single soul at the meeting. Would I have just attended the meeting, I would´ve learned some interesting facts about antibiotic resistance and some references to key papers. However, I gathered up my courage to chat to some important people over coffee break and asked a few questions that led to a long discussion over lunch with some other important people (one of whom, by the way, was telling me after I confessed I hardly knew anything about bacteria and more about malaria, that malaria research can have some really interesting insights in drug treatments in general, referring to our PNAS and PLoS Path papers, TADAAA moment!) and learned so much more. Now, I feel like these two days were time well spend (while I know I could´ve worked on important MS´s that need to get finished, I know Andrew…).

This networking thing absolutely doesn´t come natural to me. I have to convince myself that these other people won´t bite and my question surely can´t be entirely stupid. Still, I feel nervous and goofy when I am sneaking up to some ´silverbacks´ over coffee break to introduce myself and my heart is pounding out of my chest when I ask a question at the end of a talk. However, I have never regretted opening my mouth. So, here´s my advice to all starting PhD students, or even postdocs, that are afraid of asking questions or networking with strangers on conferences. Just do it. If you are planning to wait until you aren´t nervous about it, it will never happen, nervousness disappears with practice. Start with lab meetings, then try to ask a question during CIDD seminar. If you are worried that you might ask something stupid, or don´t know any question, use this trick: make yourself write up one or a few questions during every seminar. It will get your brain involved, and you´ll probably realize that often someone else is asking your question. Ask your question to other PhD students and postdocs afterwards to get your confidence up that you didn´t have a stupid question (which they never are!). Then one day, don´t think about it, raise your hand, and you´ll realize afterwards that the world still exists.

I truly think that actively participating in labmeetings, seminars and conferences will get you so much more than passively participating: not only will you learn more and generate new ideas, other people will get to know you and your thoughts too.

Well, so far my parting wisdom. Looking forward to seeing you all again (networking) at a future conference!