Everything seems harder the first time you do it.

Everything seems harder the first time you do it.

If you’ve made bread, or, for you scientists, designed PCR primers, think about the first time you did it. On the face of it these processes are simple, and share the same formula; you have a recipe, you follow it, you get the desired product. End of story. Yet, acquiring new skills often doesn’t feel simple.

I usually have some apprehension the very first time I try something – will the bread really rise like it’s supposed to? – and experience relief, satisfaction, and the sense that I’ve experienced some small miracle when ingredients have been turned into a loaf of bread, bands on a gel, etc. But the magic wears off. Later, looking back, it’s hard to remember what the big deal was.

So what makes learning new skills seem difficult?

At least two things – feel free to add more:

1) How intrinsically hard it is. Let’s face it, some things are just hard (e.g. requiring many steps, background knowledge, complex movements – see “expertise“, etc). This is related to the learning curve, or the difficulty of the new skill. Not much skill necessary to boil an egg, and quite a bit to design working PCR primers. For simpler skills, learning happens in huge leaps early on, followed by smaller gains as there is less left to know, whereas for harder tasks the climb up the curve is just one long slow haul.

2) Level of familiarity, i.e. transferrable skills. If you apply previous experiences new skills seem much easier: PCR aids learning quantitative PCR. And, we actually do get better and faster with practice; this looks a lot like improving efficiency along an experience curve to me.

Right now I’m learning how to grow Plasmodium falciparum parasites in culture.

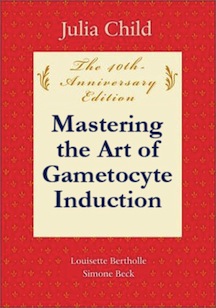

I’ve been told this is really straightforward, and the basic steps for growing an asexual culture seem to be – plus they are relatively hardy little buggers. But I’m interested in the life stage that can infect mosquitoes – the gametocytes. These are the sexual stage, the prima donna parasites, finicky about temperature changes, whether they get human or animal sera, fresh or less-than fresh RBCs, you name it. Unfortunately, even the people that do this for a living have told me gametocyte induction is really hard.

Why? Well, as best I can tell it’s a combination of slightly technical challenges (sneeze in your culture and it’s all over), and the need for experience to know exactly when to do each step. The parasites are only convinced to become gametocytes by being stressed. Without stress, the asexuals would happily keep on growing, and might never make any gametocytes. In practice, this means that after I get the parasites growing I’m then stressing them to the point where some inevitably die, more have a near-death experience, but not stressing them so much that the whole flask of parasites kicks the bucket. (I find the parasites aren’t the only ones a little stressed by this particular step). Afterwards I make every effort to placate them with a cushy environment, the freshest red blood cells available, and try to make amends (all while selectively killing the other non-gametocyte-producing stages with heparin). After several days only gametocytes are in the culture. This is way more involved than any bread I’ve ever baked.

But, as Julia Child said, “Anyone can cook in the French manner anywhere, with the right instruction” (Mastering the Art of French Cooking, introduction). [Translation – “Even Jessi can learn gametocyte induction techniques with the right instruction”]. And fortunately I have the written instruction of many other scientists that have tried this. Much more importantly I have the expert instruction of the members of the Cui lab. In particular, Feng’s advice and patient explanations continue to be invaluable in this process.

Having mentorship in learning complex techniques is vital, and nothing beats actually seeing the process through when first figuring it out. It has allowed me to jump along the experience curve to become more efficient much faster than I ever would have been able to without this type of help. With luck, and enough observation and practice, I’ll be bringing this skill to the Read/Thomas group sometime soon. I’m planning to use the same equipment and tools since familiarity makes the learning process easier, and reduces room for errors due to picking the wrong types of flasks and so on.

When an expert isn’t available there are often alternatives – perhaps this explains in part the popularity of cooking shows, or youtube instructional videos. Scientists are cluing into this – just check out the Journal of Visualized Experiments.

This week my parasites are on their way to becoming beautiful gametocytes. In fact, the precocious ones made their appearance this afternoon! They should continue to develop, barring any hurricane-related interruptions to their care. I’ll keep you posted.